|

|

|

|

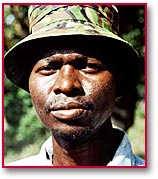

Joseph's

butterflies take flight

Twice a week

butterflies from Kenya's Arabuko Sokoke Forest fly to Europe, the United

States and Canada. Carefully collected and cocooned in special packaging

they are exported to international markets by farmers taking part in an

innovative project that protects Kenya's natural resources while generating

an income from them. Twice a week

butterflies from Kenya's Arabuko Sokoke Forest fly to Europe, the United

States and Canada. Carefully collected and cocooned in special packaging

they are exported to international markets by farmers taking part in an

innovative project that protects Kenya's natural resources while generating

an income from them.The Arabuko Sokoke National Park is the largest remaining piece of a coastal forest that once stretched all the way from southern Somalia to northern Mozambique and an internationally recognized haven for wildlife - which was why the local population wanted to tear it down. Home to at least six species of endangered birds, three types of endangered mammals, and 30 percent of Kenya's butterflies, the forest is also a refuge for baboons, monkeys and elephants which, in the eyes of the communities living on the margins of the forest, are pests. "The animals were always spoiling the crops," explains Joseph Tinga Ngomba, a local farmer. "Many farmers have been forced to abandon their homes and plots because of elephant raids." Just 80 kilometres from the city of Mombasa, the forest was also used as a source of wood for fire and construction for a rapidly growing population. Land was cleared for cultivation and animals were poached for meat. Years of these practices had already reduced the once expansive forest to a 400-square-kilometre swath. It was clear that without the support and cooperation of the local community the forest had no long-term future. So in 1993 the United Nations Development Programme's (UNDP) Small Grants Programme funded the Kipepeo Butterfly Project. The goal: to link the conservation of the butterfly habitat to the well-being of the surrounding communities by making them beneficiaries of the forest's natural biodiversity.  The first challenge was

to demonstrate that the forest could have more value intact than as land

cleared for cultivation. "People used to go into the forest to cut

timber and hunt animals," says August Hare, a Kipepeo Centre staff

member. "It took some time to convince the local people to stop

damaging the forest and learn its advantages. We taught them the processes

of butterfly farming, including how to export them." The first challenge was

to demonstrate that the forest could have more value intact than as land

cleared for cultivation. "People used to go into the forest to cut

timber and hunt animals," says August Hare, a Kipepeo Centre staff

member. "It took some time to convince the local people to stop

damaging the forest and learn its advantages. We taught them the processes

of butterfly farming, including how to export them."Butterflies are in demand in international markets. They are released in public and private gardens or purchased for special ceremonies such as weddings. Instead of throwing rice or confetti as the bride and groom leave the church, family and friends are releasing flights of colourful butterflies, creating a new custom that is more memorable and environmentally-friendly than the traditional method. Collecting and raising butterflies for export allowed people to legitimately earn a living from the forest, and be invested in preserving it. Joseph was one of the beneficiaries. Butterfly pupae fetch between US$1 to $2 each. In a good month, he earns about $80, twice as much income he earns from selling the maize he grows on his plot of land. "Until 1993 when the butterfly project was started, I was facing the problem of finding agricultural activities which would allow me and my family to survive," he says. He tried beekeeping. When that proved to be impractical for the area, Joseph turned to butterfly farming. He is one of 700 farmers who are now involved in the Kipepeo, Swahili for butterfly, project. To prevent overexploitation, the butterfly collection process is carefully controlled. After receiving training from Kipepeo, the farmers organized into groups of 10 to 12. They choose just one representative who is authorized to go into the forest to catch the butterflies. Joseph, the representative from his group, explains the process: "I go to the forest and catch female butterflies. I put them in a closed shed. The butterflies lay eggs. When the larvae come, I divide them among the members of my group. They are fed with special leaves from plants collected from the forest until they turn into pupae. The pupae are packaged and exported by courier mail." The Arabuko forest is famous world wide for its 260 different species butterflies. Some such as the Blanda Charaxes, are very rare and can only be found in this forest; or the Blackswordtail which is so attracted to water that after a heavy rain clouds of them can be seen around puddles in the forest. By 1999, the forest earned $80,000 from butterfly sales. In comparison, tourism brought in $3,000 and forest products brought in $9,000. Started with an initial grant of $50,000, the Kipepeo project is now economically self-sustaining. Word of the project's success has spread, inspiring other donors to contribute. The IUCN Netherlands Committee and the Japanese Government helped finance a water system that benefits 20,000 people. Kipepeo's project coordinator was invited to initiate similar programmes in neighboring Uganda and Ghana. Butterfly farming doesn't bring in enough to support him entirely but it is a good complement to his other activities. "With the income from butterfly farming I bought two fishnets," says Joseph. "With this I added to my income, providing food to my wife and five children." |